Purpose: To study the contribution of quarantine with online work and education to exacerbating digital eye strain and causing possible refractive changes. To illustrate the prevalence of mask associated dry eyes and potential increase use of contact lenses.

Methods: This is a questionnaire-based cohort study from Lebanon during the period between July 1 and October 1, 2021. The questionnaire consisted of 10 multiple choice questions in. The included age group was between 5 and 50 years old.

Results: The total number of questionnaires was 100. The mean age was 25.8 years. 73% of patients were involved in online work or education during COVID pandemic and these were divided into subcategories. 83% of the patients reported an increase in screen time during quarantine. Furthermore, 59% declared worsening of their dry eye symptoms, developing dry eyes, had ocular fatigue and/or headache secondary to increased screen time (70% of the participants had an existing chronic dry eyes).

Crosstabulation analysis showed that out of the patients who reported increased in digital eye strain symptoms, 83.1% had online work or education (28.8% had online school classes, 18.6% had online university classes and 35.6% were involved in online work) while 16.9% weren’t involved in any online activity (P=0.011).

Conclusion: Patients who switched to online work and education during COVID-19 pandemic had significantly higher incidence of digital eye strain. No significant change in refraction was noted as compared to patients without online work and education. Mask associated dry eyes was noted in a large number of patients.

Cornea; Ocular surface; Eye strain; Dryness; COVID-19

With the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, the world was impacted on both institutional and personal levels. With the main focus on halting the spread and transmission of the disease, millions of individuals shifted from personal attendance to home quarantine, online work and education with strict personal hygiene and protection regulations. This transition manifested as an increase in the time spent using digital devices such as smartphones, tablets, laptops or desktops as well as using the face mask as a basic personal protective equipment. The prolonged digital device usage has led to increased complaints of dry eyes, headaches, itching, blurring of vision and foreign body sensation; which all fall under the umbrella of Digital Eye Strain (DES) [1]. Digital eye strain is a phenomenon that involves a compromise of the ocular surface secondary to decreased blinking rate while using any digital device [2]. This leads to increased tear film evaporation with diminished mechanical stimulation of the Meibomian glands and subsequently inadequate replenishment of the lipid layer. Another component of digital eye strain is the involvement of the intraocular and extraocular muscles to provide accommodation and convergence with subsequent eye fatigue and headache after maintaining this state for a prolonged period of time [3]. The prevalence of DES has been increasingly reported among school and university students taking online classes [4,5]. On the other hand, the widespread use of face masks during the pandemic has led to the emergence of complaints such as skin irritation and sweating, eyeglasses fogging and difficulty breathing [6]. Literature has been enriched with studies involving the ophthalmic side effects of prolonged face mask wearing especially that related to worsening dry eye symptoms which was first described in the literature as mask associated dry eyes and given the acronym “MADE” [7]. In this article, we demonstrate the contribution of quarantine with online work and education to exacerbating digital eye strain and causing possible refractive changes. Moreover, we illustrate the prevalence of mask associated dry eyes and potential increase use of contact lenses.

This is a questionnaire-based cohort study analyzing the effect of increased screen time among patients who had online work and education during COVID-19 pandemic quarantine versus those who didn’t have any online chores. The study included patients visiting a central ophthalmology specialty hospital in Lebanon during the period between July 1 and October 1, 2021. The questionnaire consisted of 10 questions which were mainly Yes or No questions and multiple choices to choose from in both Arabic and English languages to reflect subjective measurement along with OSDI score for objective evaluation of dry eyes. The age group for the patients eligible to fill the questionnaire was chosen to be between 5 years and 50 years old. Patients with keratoconus, trauma and glaucoma were excluded from the study since they already have an abnormal ocular surface secondary to medication or mechanical disruption. The questionnaire was filled by the patient before undergoing the slit lamp exam to prevent any visual inconvenience. Before filling the questionnaire, the participant was informed about the length of the questionnaire and that the data will be used for research purposes while maintaining full anonymity of the participant. All the data obtained was statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software®. Cross tabulation and Chi square test were used to compare variable within different categories. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The total number of questionnaires filled within the aforementioned time frame was 100. The mean age of the participants was 25.76 years. 24% of the participants were 18 years old or below, 24% between 19 and 25 years, and 52% of age 26 and above. Among the participants, 47% (n=47) were males and 53% (n=53) were females. 17% (n=17) of the patients had no refractive error, 63% (n=63) were myopic while 20% (n=20) were hyperopic. 73% (n=73) was the percentage of participants who were involved in online work or education and these were divided into three subcategories:

Online school education 25% (n=25), online university education 18% (n=18) and online work from home during quarantine 30% (n=30). Patients who weren’t involved in any online activity during quarantine comprised 27% (n=27). 28% (n=28) of the accomplices reported starting to wear or change their eyeglasses due to adjustments in their refractive error in the past 2 years. Furthermore, 83% (n=83) of the patients conveyed an increase in screen time during quarantine. In addition, 70% (n=70) of the participants described already having symptoms of dry eyes and using eye lubricant to relieve these symptoms with 59% (n=59) declaring worsening of their dry eye symptoms, developing dry eyes, had ocular fatigue and/or headache because of increased screen time. On another hand, 44% (n=44) confirmed experiencing mask associated dry eyes alongside 20% (n=20) of the participants declaring increased preference to wear contact lenses instead of eye glasses to avoid the fogging effect secondary to face mask wearing. As for the use of blue light filter glasses, only 12% of the participants were more comfortable while using them, 5% report not being comfortable with their use, while 83% did not use glasses with blue filter at all.

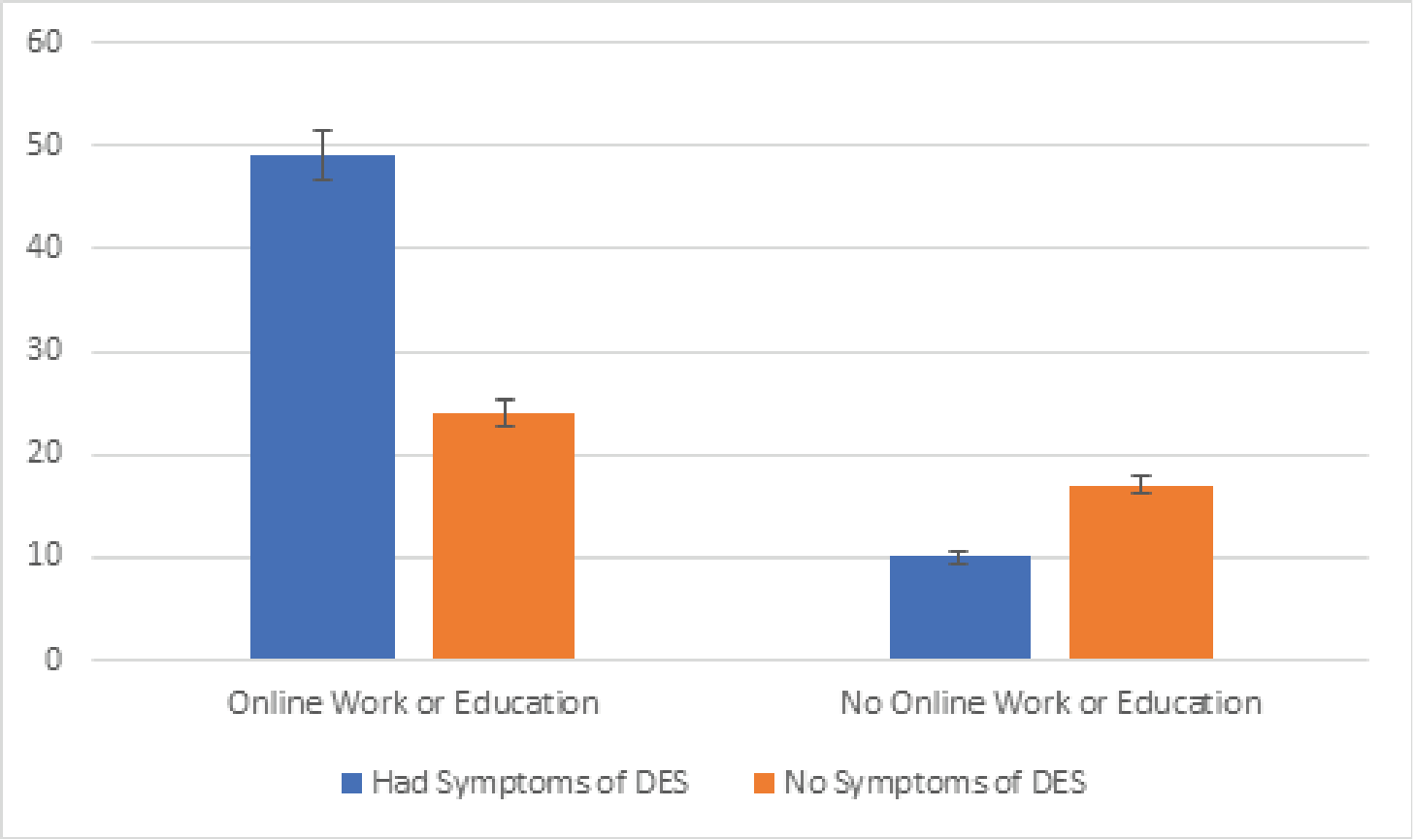

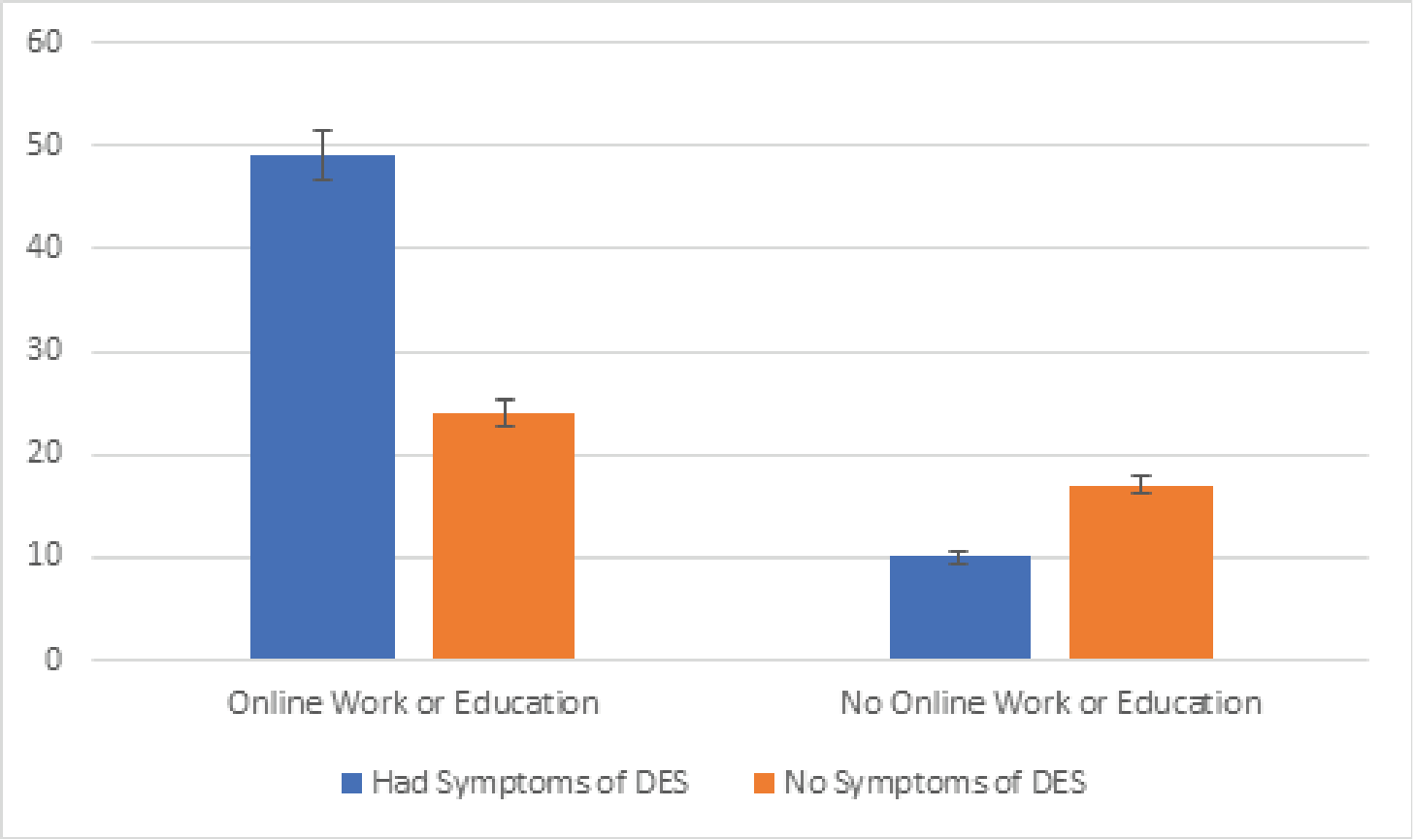

Crosstabulation analysis showed that the prevalence of DES among individuals exposed to online platforms for work or education was 67.1%, which is statistically significant (p <0.05) compared to those with no online tasks. Moreover, out of the patients who reported increase in digital eye strain symptoms, 83.1% (n=49) had online work or education while 16.9% (n=10) weren’t involved in any online activity, with results showing statistical significance (p <0.05). A column chart representing the number of patients reporting digital eye strain among online and non-online categories is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Column Chart representing the count of patients with Digital Eye Strain Symptoms in those who had online work or education versus those who didn't (95% CI with p-value <0.05).

Symptoms of DES were variable among individuals using digital devices for different purposes. In our survey, 68% of school students using online education tools report symptoms of DES, 61.1% of university students using online education tools report symptoms of DES, and 70% of those working from home report DES symptoms, compared to 16.9% of individuals not belonging to any of these categories who state experiencing DES symptoms (table 1) The criteria for increased screen time is based on measuring the hours spent on electronic devices (other than the usual time spent on cellphones) which are usually used for studying or working online (online school/university education and online work) such as tablets, computers etc... Spending 3 or more hours on the fore-mentioned screens (not including cell phones) for online chores, categorize the participant as “increased screen time” due to online school education, university education and/or online work.

Table 1: representing the percentages of patients with Digital Eye Strain symptoms among the different subcategories of online versus offline categories

Online Work or Education |

Had Symptoms of DES from Increased Screen Time |

Didn’t Have Symptoms of DES from Increased Screen Time |

No Online Work/Education |

16.9% |

41.5% |

Online School Education |

28.8% |

19.5% |

Online University Education |

18.6% |

17.1% |

Online Work |

35.6% |

22.2% |

In studying the impact of online exposure as work or education on refraction changes by asking whether the participants started wearing glasses or changed their glasses prescription in the past 2 years, results were insignificant (p=0.779). Of the individuals using online resources for previously mentioned purposes, 28.8% report changes in refraction as compared to 25.9% in individuals not using online resources. Of the patients experiencing dry eyes, 65.7% were myopes, 18.6% were hyperopes, and 15.7% were emmetropes.

Health restrictions secondary to COVID-19 pandemic have driven the implementation of online education and work in most institutions, making increased time spent on digital devices inevitable. Personal activities including family calls, shopping and entertainment have been also shifted to digital platforms, along with an emphasis on the role of social media as a means for communication amid the absence of social visits and meetings [8]. In our study, the age range of the participants eligible to fill the questionnaire was chosen to be between 5 and 50 years. We find this population the most ideal to represent the individuals exposed to digital devices and to eliminate any confiding factors related to aging that may interfere with interpreting the symptoms of DES. The mean age of the participants was 25.76 years, with 24% of age 18 years or bellow, 24% between 19 and 25 years, and 52% of age 26 and above. This reflects on the type of online exposure in which the results were comparable, with 25% experiencing online schooling, 18% experiencing online university education, and 30% falling under the category of online work from home. 27% were not engaged in either of the preceding online activities. However, of the latter population, we could not stratify users of digital devices for entertainment, shopping and social media, so we shall assume that even the individuals who were not engaged in online studying or working are users of digital devices for the previously mentioned purposes.

Portello et al. divided DES symptoms into two categories: symptoms related to accommodation including blurry vision for near objects, headache, eyestrain, and those related to dryness including burning, itching, watering, redness, foreign body sensation, eyelid heaviness and light intolerance [9]. Segui et al. developed the Computer Vision Questionnaire (CVS-Q), which evaluates the intensity and frequency of 16 eye strain related symptoms, and is considered a verified and validated tool to diagnose DES [10]. CVS-Q was used in several comparable studies to ours, however most of these were conducted among school or university students, who are more compliant to completing such a lengthy questionnaire. In the questionnaire designed in our study, symptoms of DES were referred to as dryness, headache and ocular pain, as we considered that further elaboration on symptoms would make the questionnaire hectic for the patients to complete. The individuals involved in our study are patients presenting to a specialty hospital with no selection based on educational background. Thus, for the purpose of compliance and practicality, we chose to include some of the symptoms of DES, and we considered a positive response to be indicative of DES.

Our results were statistically significant (p<0.05) for the prevalence of DES among individuals involved in online activity, where 67.1% of users of online tools for work or education report DES symptoms, and 83.1% of patients reporting increase in DES symptoms were users of online platforms. Besides, 68% and 61.1% of school and university students, respectively, using online education tools experienced symptoms of DES, and 70% of those working online from home reported DES symptoms. Such results are comparable to other studies. The prevalence of DES among a population of school students taking online classes in a study conducted in India was found to be 50.23%, which accompanies the increase in number of hours spent on digital devices, as 36.9% of children report spending more than 5 hours on such devices compared to only 1.8% of children spending this amount of time in the pre-COVID era [4]. This percentage soars to 89.9% in a questionnaire based study involving university students [5]. It has been well established that university students are prone to develop computer vision syndrome secondary to the study burden and heavy use of digital devices, with incidence ranging from 71.6% to 94.5% [11,12]. Although not shown in our study, students were found to experience more symptoms than workers, which may be attributed to their abrupt increase in screen time as they are previously less exposed to digital devices as education tools [8]. The variable prevalence of DES in our study compared to others can be attributed to the different population and type of questionnaire.

Duration of time spent on digital devices was considered a significant risk factor for the prevalence and severity of DES [13,14]. According to the American Optometric Association, digital eye strain develops with as little as two hours of continuous digital device usage per day [15]. 83% of the individuals involved in our study report increase in time spent on digital devices during quarantine. In a study conducted by Bahkir et al in India among 407 individuals of different occupations and age groups, 93.6% reported increase in time spent on digital devices after lockdown [8]. The study established a significant correlation between increase in screen time and frequency and severity of ocular symptoms [8].

In our survey, 47% of the participants were males and 53% were females. The prevalence of DES in females was 73.6% which is more than that in males 66%., with no statistical significance. Females were more affected than males in several studies, which may be explained by the higher incidence of autoimmune conditions and headache disorders in females predisposing them to dry eyes and visual symptoms [16,17,18]. Besides, cosmetic products can cause tear film instability which might exacerbate the symptoms of dryness and ocular irritation [19].

In studying the impact of prolonged digital device use on the change in refraction necessitating eye glasses or change in glasses prescription, results were insignificant (p=0.779). Only 28.8% of the individuals using online resources report refraction changes in the past 2 years as compared to 25.9% not using online resources. Of the patients experiencing dry eyes, 65.7% were myopes, 18.6% were hyperopes, and 15.7% were emmetropes. From our study, we cannot draw a clear relationship between the prolonged use of digital devices and the development of refractive error. Yet, it is important to note that the increase in near work activities and the accompanying indoor lifestyle imposed by the extended lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with increased risk of myopia [20,21].

A questionnaire-based study in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that 18.3% of the 3,605 individuals from the general population involved experienced MADE, with worsening of their dry eyes symptoms from wearing a face mask [22]. Our results reveal that 44% of the involved participants complained of MADE, which may be an overestimated number attributed to a difficulty in subjectively delineating whether dryness is exacerbated by mask use per se or by contribution from other factors such as digital device use, environmental factors, or even previous infection with COVID-19. Moreover, the preference in the use of contact lenses over spectacles while using face masks showed no statistical significance. In a prospective randomized study comparing ocular related symptoms among 2 arms: individuals wearing spectacles and those wearing contact lenses, significant differences were observed supporting that contact lenses are a better vison correction option than spectacles while wearing a face mask [23].

Only 12% of the participants report feeling more comfortable while using blue light filter eyeglasses, while 83% did not use it. The use of blue light filter glasses may be helpful in decreasing asthenopia and reducing circadian disturbances although their use has not been recommended by American Academy of Ophthalmology up till date [1,8].

Our study had a few limitations. The prevalence of DES among our patients may not correlate with its prevalence in the general population. The patients presented to an ophthalmology specialty hospital seeking medical attention for ocular symptoms, which by default places them at a greater probability of reporting symptoms related to ocular strain and dryness. Besides, the study was based on a self-designed non-standardized questionnaire with emphasis on a few symptoms of eye strain. No objective clinical assessment of ocular surface health was done, which puts the results under subjective error and responders’ bias.

In conclusion, patients who switched to online work and education during COVID-19 pandemic had significantly higher incidence of digital eye strain. These patients were of a younger age group. However, no significant change in refraction was noted as compared to patients without online work and education. Mask associated dry eyes was noted in a large number of patients. Our results were consistent with other studies from other countries. Ophthalmologists and health care professionals should be aware about these findings when examining patients with eye strain and dryness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

No ethical approval is required for this research article since informed consent has been obtained from the patients who filled the survey for this article and no experimentation was done on any human or animal subjects.

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients/ guardians of the children involved in this article prior to completing the required survey.

The data associated with this paper was obtained from the survey filled by the patients and their corresponding archived files. The data could be accessed after the approval of the Chairman of the Department.

- Sheppard A., Wolffsohn J (2018) Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 3: e000146. [Crossref]

- Patel S., Henderson R., Bradley L., Galloway B., Hunter L (1991) Effect of Visual Display Unit Use on Blink Rate and Tear Stability. Optometry and Vision Science 68: 888-892. [Crossref]

- Bhootra A (2014) Basics of Computer Vision Syndrome. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers.

- Mohan A., Sen P., Shah C., Jain E., Jain S (2021) Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian J Ophthalmol 69: 140. [Crossref]

- Reddy S., Low C., Lim Y., Low L., Mardina F., et al. (2013) Computer vision syndrome: a study of knowledge and practices in university students. Nepalese Journal of Ophthalmology 5: 161-168. [Crossref]

- Scheid J., Lupien S., Ford G., West S (2020) Commentary: Physiological and Psychological Impact of Face Mask Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 6655. [Crossref]

- White DE. BLOG. MADE: a new coronavirus-associated eye disease 2020.

- Bahkir F., Grandee S (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on digital device-related ocular health. Indian J Ophthalmol 68: 2378. [Crossref]

- Portello J., Rosenfield M., Bababekova Y., Estrada J., Leon A (2012) Computer-related visual symptoms in office workers. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 32: 375-382. [Crossref]

- Seguí M., Cabrero-García J., Crespo A., Verdú J., Ronda E (2015) A reliable and valid questionnaire was developed to measure computer vision syndrome at the workplace. J Clin Epidemiol 68: 662-673. [Crossref]

- Gammoh Y (2021) Digital Eye Strain and Its Risk Factors Among a University Student Population in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. [Crossref]

- Kharel (Sitaula) R., Khatri A (2018) Knowledge, Attitude and practice of Computer Vision Syndrome among medical students and its impact on ocular morbidity. J Nepal Health Res Counc 16: 291-296. [Crossref]

- Ichhpujani P., Singh R., Foulsham W., Thakur S., Lamba A (2019) Visual implications of digital device usage in school children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol 19: 76. [Crossref]

- Kanitkar K., Carlson A., Richard Y (2021) Review of Ophthalmology. 12th ed.

- Computer vision syndrome (CVS) (2020) American Optometric Association.

- Wang H., Wang P., Chen T (2017) Analysis of Clinical Characteristics of Immune-Related Dry Eye. J Ophthalmol 1-6. [Crossref]

- Matossian C., McDonald M., Donaldson K., Nichols K., MacIver S., (2019) Dry Eye Disease: Consideration for Women's Health. J Women’s Health 28: 502-514. [Crossref]

- Ahmed F (2012) Headache disorders: differentiating and managing the common subtypes. Br J Pain 6:124-132. [Crossref]

- Wang M., Craig J (2018) Investigating the effect of eye cosmetics on the tear film: current insights. Clin Optom (Auckl) 10: 33-40. [Crossref]

- Morgan I., Ohno-Matsui K., Saw S (2012) Myopia. The Lancet 379: 1739-1748

- Saw S., Chua W., Hong C., Wu H., Chan W., et al. (2002) Nearwork in early-onset myopia. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 43: 332-339. [Crossref]

- Boccardo L (2021) Self-reported symptoms of mask-associated dry eye: A survey study of 3,605 people. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 101408. [Crossref]