Health fairs are an example of community-academic partnerships (CAP) with the role of advancing community health by involving multiple stakeholders in implementing interventions. Health fairs integrate input and support from community partners to specifically address the needs of a community through surveys, screening, and education.

Objective: The purpose of this analysis is to further identify community needs and optimize our community-academic partnership to improve community health.

Methods: Medical and nursing students from Texas A&M Health Science Center collaborated with a local Title 1 elementary school to host a health fair where health screenings, health education, and community resources were provided to parents. A bilingual 13-question feedback survey was distributed to assess perceived healthcare needs, screening results, and identify areas of improvement for the fair.

Results: From 2017-2019, the average blood pressure and blood glucose screening results were consistently within normal ranges though we identified several participants with abnormal results. Using survey results, we identified which booths were most utilized including blood glucose screening, blood pressure screening, and health habits/nutrition booths. Additionally, we identified consistently reported planned behavior changes after attending our health fair including “exercise more,” “try new recipes,” and “visit a healthcare provider.”

Conclusions/Relevance: Through analyzing data collected over a three-year span (2017-2019), we were able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of our event and target specific community needs to further improve our CAP with a focus on primary intervention. We believe our study may serve as a valuable resource for future community-academic partnerships that further student education and community health.

Student-Led Health Fair; Community-Academic Partnership; Quality Improvement

Community health fairs are a growing means to educate and evaluate the health of the public [1]. Student-led fairs specifically encourage a partnership between medical and/or nursing schools and the surrounding community in order to strengthen trust and communication with health-care professionals [2]. Additionally, student-led health fairs allow students to experience first-hand what health deficits their local community have, whether measured or perceived [3]. In the literature, community health fair attendees have been shown to make behavioral changes, including risk reduction, after attendance of the fair [4]. Health fairs also serve as a means for screening, potentially identifying disease states in people who would otherwise be unaware [5].

Health fairs are an example of community-academic partnerships (CAPs) with the role of advancing community health by involving multiple stakeholders in implementing interventions [6]. CAPs utilize community stakeholders who have knowledge of the community needs, allowing health and academic entities to act on them and create interventions as needed [7]. Health fairs integrate input and support from community partners to specifically address the needs of a community through tools including surveys, screening, and education [8]. CAPs are invaluable in advancing the health of the public and must be founded on values trust, defined goals, respect, and sustainability [9].

The CAP outlined here involves businesses and sponsors within the community to educate community members, as well as both nursing and medical students to conduct health screenings and provide information about healthy living. Attendees of the fair were asked to participate in a survey to gauge their interest, their perceived needs and personal health states, as well as their overall utilization of health resources both at the fair and in the community. Data from 2017-2019 was analyzed to longitudinally compare the needs of the community over time. This data will be utilized to tailor the fair to both the needs and desires of the community to improve participation and utilization of resources provided.

Additionally, the purpose of this analysis is to optimize our CAP to improve community health. The need to strengthen relationships between the academic institutions and community resources is important, as each entity has a unique set of skills and resources that can benefit and realize a shared goal [10]. We will use the data acquired to further our partnerships with stakeholders and community members.

Schools with a high number or high percentage of children from low-income families are eligible for Title 1 funding [11].

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) is a national nonprofit organization dedicated to innovating the quality and delivery of healthcare. Our local Round Rock chapter is composed of medical and nursing students. In 2017, the chapter began a partnership with a local elementary school in Round Rock ISD (RRISD) to provide a health fair for children and parents. Since then, IHI Round Rock has held its Community Health Fair annually. Games and activities for children were held on site by student volunteers. Sponsors from the community provided booths with health information, activities, and local resources for families.

Participants

The school has approximately 800 students and is located in a community with 68.4% of students coming from economically disadvantaged families (RRISD). The health fair was held at the school following a 1st and 2nd grade choir concert in 2017, and following an established monthly parent potluck in 2018 and 2019. From 2017 to 2019, 164 adults and 134 children attended the health fair for a total of 298 attendees.

Measures

Starting with the 2017 fair, a bilingual, one-page questionnaire was handed out to adults at the health fair as part of a mixed-methods approach. Survey respondents were asked to report which booths they visited during the health fair. Survey respondents were also asked to select options that reflected how they planned to change their lifestyle in the future after attending the health fair. The listed options were: “exercise more”, “visit a health care provider”, “read pamphlets” (provided at the health fair), “try new recipes”, “use a helmet,” and “do not plan to use the information.” Beginning in 2018, participants were asked to provide feedback about the health fair and respond on a scale of 1-7 from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Questions included their intention to establish a relationship with a healthcare provider, or follow-up with a pre-existing provider, and if they believed annual visits with a healthcare provider were important for staying healthy. This questionnaire was designed to assess parent attitudes toward health and gather parent feedback on ways to improve future health fairs.

The same scale was provided for rating the overall quality of the health fair, and their likelihood to attend another health fair in the future. There was a free-response field allowing for comments and recommendations on how to make the health fair more helpful.

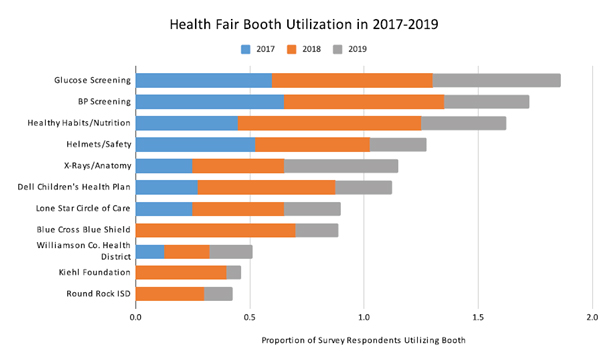

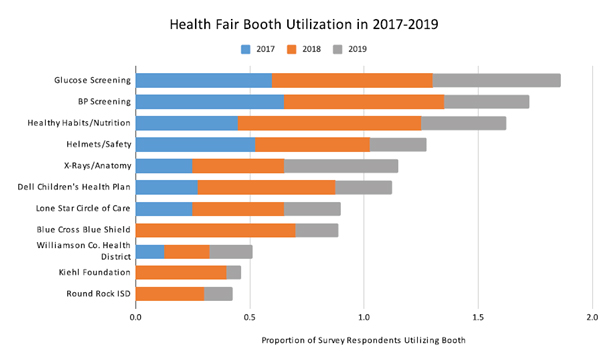

When surveyed about health fair booth utilization, participants consistently reported that the blood glucose screening, blood pressure screening, and health habits/nutrition booths were most frequently visited across 2017-2019 (Figure 1). Notably, in 2019, the x-ray booth increased in utilization while the health insurance related booths declined in utilization.

Figure 1. Health Fair Booth Utilization Represented By Proportion of Survey Respondents for Each Booth from 2017-2019

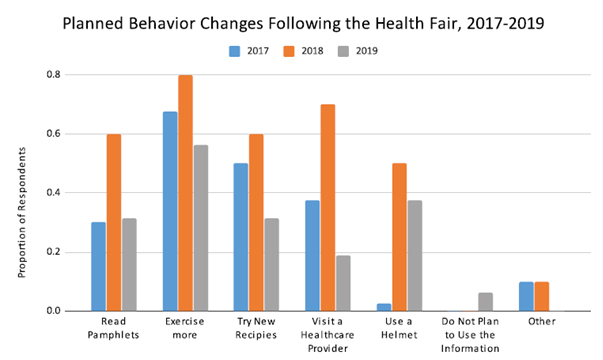

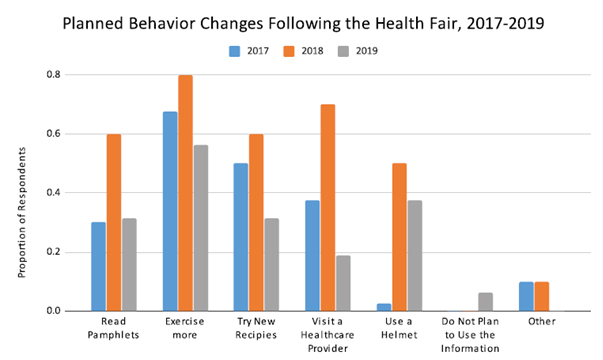

From 2017-2019 when surveyed about planned behavior changes following the health fair, 55-80% of participants reported that they planned to “Exercise more,” which was the most popular response. Additionally, participants responded that they would “try new recipes,” “read pamphlets,” “visit a healthcare provider,” and “use a helmet,” in order of decreasing popularity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Planned Behavior Changes Following Health Fair Represented By Proportion of Survey Respondents for Each Behavior Change Option from 2017-2019

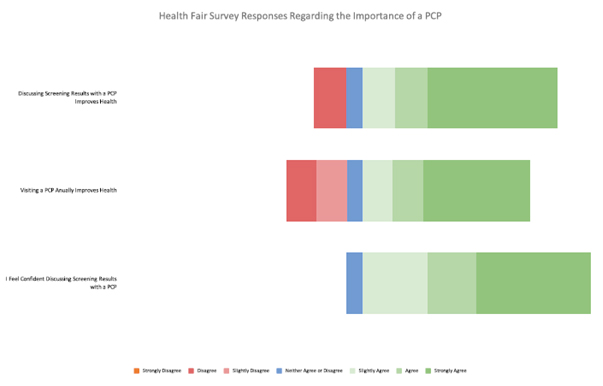

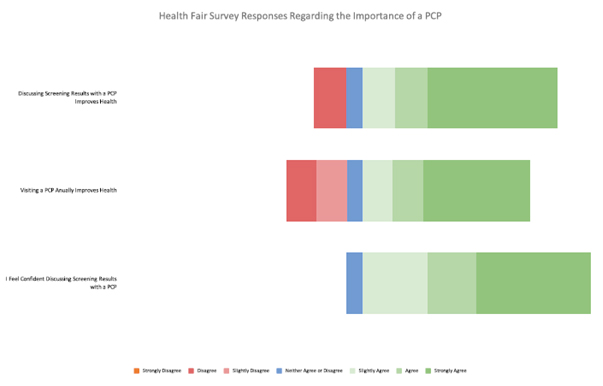

In response to the 2018-2019 survey, a majority of respondents indicated they agreed that discussing their screening results with a healthcare provider was important, and that people in their community believe visiting a healthcare provider annually is important for staying healthy (Figure 3). Of the 77 participants who had a blood pressure screening, 34% of the readings were identified as abnormal according to the ACC/AHA guidelines. 10% were considered elevated, (systolic 120-129 and diastolic <80) 16% were stage 1 hypertension, (systolic 130-139 or diastolic 80-89) and 8% were stage 2 hypertension (systolic at least 140, diastolic at least 90) readings [12]. Of the participants with abnormal blood pressures, 12% answered they had previously been told they have high blood pressure, and 31% indicated they plan to follow up with a healthcare provider regarding their abnormal results [13].

Figure 3. Participant Perception of Primary Care Follow-Up Based on 7-Point Likert Scale

85 participants had their non-fasting blood glucose level (BGL) checked, and 8% had a non-fasting BGL greater than 140, with only 1 of these participants self-identifying as diabetic [14]. All participants in the screening portion of the health fair were provided with a copy of their results that included written instructions to follow up with a PCP.

The event was fully student-run by an interdisciplinary team. Each year, the design of the health fair was based on guidelines from published literature and data and feedback from the event itself to better meet the needs of the community. As is the nature with community health fairs, the IHI team continued to work with an established community partner and developed a strong reputation and consistent presence over the past 3 years. We continued to use bilingual surveys and health screenings to benefit the local community. We utilized survey responses over a 3-year time span to analyze trends and consistent strengths and weaknesses in our event.

The booth utilization data provided insight as to which resources were most appealing to the community and shared characteristics of the frequently utilized booths. In general, resources with clear benefits and concrete resources were the most popular. We found that booths with visually appealing displays and hands-on activities and resources were more frequently visited. The booths offering blood pressure and blood glucose screening that provided a tangible benefit such as health information were also consistently popular throughout 2017-2019. Finally, we noted that the X-ray and Healthy Habits booths that provided hands-on interaction and simple, explicit advice were consistently well-utilized. In our next health fair, we will integrate interactive and incentives into our less popular primary care and health insurance booths to further encourage participants with abnormal screening values to seek long-term care.

We also analyzed trends in survey responses regarding how our participants planned to adjust their lifestyle habits after attending the health fair. Since “exercise more” was the most frequent response, we plan to include a booth from a local fitness center or community vendor that provides information and opportunities for participants to start an exercise regimen. Many participants also indicated that they planned to “read more pamphlets” and “try new recipes.” We can utilize this information to optimize our health fair by providing further resources tailored to their responses such as exercise regimens, healthy recipes, and health information pamphlets. In contrast, we saw a decline in 2019 regarding the number of participants planning to establish a relationship with a healthcare provider. We plan to provide contact information and resource pamphlets from local primary care providers to facilitate the process of obtaining professional healthcare for our participants.

In comparison to 2017 (40 responses), we noted that 2018 (10 responses) and 2019 (16 responses) had significantly lower numbers of survey responses. We hypothesize that the lower number of survey responses could be due to the nature of survey collection. In 2019, surveys were placed in a location at the exit near the end of the fair setup. We believe that the location of the responses was not conducive to response rate as participants were preparing to leave and not motivated to complete our surveys. In the future, we plan to adjust the location of our surveys and provide a small non-financial incentive to complete them. We believe that this will improve our survey responses and provide us with more valuable, representative data.

While we had a small sample size for blood pressure and blood glucose screening, we detected several participants that had abnormal results. Given the nature of health fairs, quantitative data is presented using descriptive statistics based only on the responses of attendees. The health fair did not serve as a diagnostic or treatment tool. All participants were encouraged to follow up with a primary care provider, and those with abnormal readings were reassured that an elevated blood pressure or glucose level did not equate to a diagnosis of hypertension or diabetes.

Rather, we hope that empowering participants with screening results, whether normal or abnormal, and health information, may promote further follow-up with a primary care physician. It is important to the costs and harmful effects of unnecessary tests in healthy patients. However, there is value and improved outcomes for asymptomatic patients who have established primary care providers [14]. Thus, we hope that noninvasive, inexpensive screening combined with education may encourage participants to establish care with a primary physician regardless of results.

The longitudinal aspects of our annual health fair provide valuable insight for future events and other similar community fairs. Events like this should focus on providing simple health education and screening and motivating participants to follow-up with a healthcare provider and take an active role in their own health. Providing primary prevention methods such as wearing a helmet, healthy eating, and exercise and providing information and outreach from local providers can aid community members in establishing healthy habits. Events should also have booths that provide hands-on interaction and pamphlets that allow patients to learn and retain basic health information. Additionally, all community health events should seek feedback from attendees and enhance their approach based on community needs. We also note that our decline in survey participation necessitates a deliberate method of collection, with survey booths placed in accessible and highly trafficked areas, and some incentive for survey completion.

Based on the successes and evolution of this event, the authors recommend that more health care providers and students seek opportunities to establish long term relationships with well-established community partners. We believe that collecting screening and survey results is valuable for understanding the strengths and weaknesses of such events. We advocate that community health fairs are beneficial events that positively impact the local communities and student education.

The IHI Round Rock chapter would like to thank the students, teachers, and staff of Union Hill Elementary school. Thank you to the Texas A&M Colleges of Medicine and Nursing students and faculty, the University of Texas Hispanic Health Professionals organization, RRISD Food Services and Parent Programs, and all of our local sponsors. We appreciate your volunteering of time and resources to support our CAP.

IRB: Approval was waived for the study by the Texas A&M University IRB.

Statement of Support: No material support was provided for this article.

Conflict of Interest: The authors do not have conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Burron A, Chapman LS (2011) The use of health fairs in health promotion. Am J Heal Promot 25. [Crossref]

- Salerno JP, McEwing E, Matsuda Y (2018) Evaluation of a nursing student health fair program: Meeting curricular standards and improving community members’ health. Public Health Nurs 35: 450-457. [Crossref]

- Squiers JJ, Purmal C, Silver M, et al. (2015) Community health fair with follow-up. Med Educ 49: 526-527. [Crossref]

- Ness KK, Gurney JG, Ice GH (2003) Screening, Education, and Associated Behavioral Responses to Reduce Risk for Falls Among People Over Age 65 Years Attending a Community Health Fair. Phys Ther 83: 631-637. [Crossref]

- Deane KD, Striebich CC, Goldstein BL (2009) Identification of undiagnosed inflammatory arthritis in a community health fair screen. Arthritis Care Res 61: 1642-1649. [Crossref]

- Ezeonwu M, Berkowitz B (2014) A Collaborative Communitywide Health Fair: The Process and Impacts on the Community. J Community Health Nurs 31: 118-129. [Crossref]

- Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B (2016) Community-Academic Partnerships: A Systematic Review of the State of the Literature and Recommendations for Future Research. Milbank Q 94: 163-214. [Crossref]

- Hamilton KC, Henderson Mitchell RJ, Workman R, et al. (2017) Using a Community-based Participatory Research Approach to Implement a Health Fair for Children. J Health Commun 22: 319-326. [Crossref]

- Wolff M, Maurana CA (2001) Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health: A qualitative study of perspectives from communities. Acad Med 76: 166-172. [Crossref]

- Weinstein JN, Geller A, Negussie Y, et al. (2017) Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. National Academies Press. [Crossref]

- Title I (2020) Part A Program. [Crossref]

- Understanding Blood Pressure Readings (2020) American Heart Association.[Crossref]

- Diagnosis | ADA 2020. [Crossref]

- Levine DM, Landon BE, et al. (201) Quality and Experience of Outpatient Care in the United States for Adults with or Without Primary Care. JAMA Intern Med. 179: 363-372. [Crossref]