This article critically examines the ongoing scientific quest to identify dark matter, arguing that the search is fundamentally misguided due to a misunderstanding of the nature of mass. The author contends that what is sought as "dark matter" is not a conventional, invisible mass, but rather the "transverse mass" which is always associated with a mass in motion- which is described mathematically as a complex magnitude with both real and imaginary components.

Drawing on the works of Lorentz and Einstein, the article explores how relativistic effects change the stationary observer's perception of a mass in motion, which is seen as composed by an inertial mass [called longitudinal] responsible for the gravitational field and a mass transverse to the motion that generates a gravito-magnetic field and that is identified with the kinetic energy.

The discussion extends to the implications for galactic dynamics, suggesting that the effects attributed to dark matter may instead arise from the gravito-magnetic fields generated by the transverse mass associated with the longitudinal mass of the stars in motion. The article concludes that the elusive nature of dark matter stems from a conceptual oversight: the missing mass in the universe may already be accounted for as energy associated with motion, rather than as an undiscovered form of matter.

longitudinal and transverse mass; gravito-magnetic field; spiral galaxies; mass and energy; nature of mass; contraction of space-time; transformation equations

In his recent paper "Dark Matter - Transvers Mass", the author maintains that dark matter cannot be detected because it is not a mass as conventionally conceived, but rather an "imaginary" mass. Imaginary not because it is the product of imagination, but because it is expressed by what, in mathematical terms, is called a "complex magnitude", formed by a real term plus an imaginary component. It is identified as a "transverse" mass, so called because it is a mass associated with every mass in motion but shifted towards an imaginary direction normal to the motion. Being "imaginary", it is not visible and not detectable as a mass but only as energy. The aim of this paper is to provide arguments supporting those affirmations

The transverse mass was introduced by Lorentz, closely followed by Einstein in his work of 1905. It is defined as "the ratio between the force applied perpendicularly to the direction of motion and the resulting acceleration," in opposition to the "longitudinal mass," defined as "the ratio between the force applied in the same direction of the motion and the resulting acceleration".

Soon Einstein abandoned the concepts of longitudinal and transverse mass. For him, mass is identified with the inertial mass, a physical magnitude that quantifies a body's resistance to acceleration when subjected to a force. It is defined as "the ratio between the force applied to a body and the resulting acceleration it undergoes". A definition that matches those of longitudinal and transverse mass. None of them, in fact, specify what the mass actually is.

Later on, Einstein identified the mass with energy, linking the concept to that of motion, because the value of the mass increases with the increase of its velocity. It does not seem, however, that this definition was useful for the search of dark matter, as nobody is looking for an invisible mass on form of energy. The ongoing search for the dark matter shows that the concept of mass is anything but clear in the scientific world.

The Concept of Motion and the Space-Time

The problem with all definitions of mass is that they are invariably associated to the concept of motion and therefore of velocity.

This concept is essentially relative. There is no absolute velocity, which would only make sense in a Newtonian universe, with absolute space-time. It only makes sense between an observer and an object moving relative to him. But to give the velocity a definite value we need to have a refence frame where the value of both, the space and the time, is definite, and the observer

is stationary with respect to it. This is a Cartesian RF which "simulates" an absolute space-time, allowing the observer to give the velocity a definite value. But that value is not absolute, it is only defined in relation to that observer, and this is an essential specification missing in the above definitions of mass.

To analyse what happens with the motion between the two subjects, a second RF, also cartesian with the origin on the object (therefore stationary with respect to it) is needed. This RF too "simulates" an absolute spacetime.

We have, then, two RFs in motion with respect to each other and we can describe the motion of objects either from one or the other of them. The typical example given in classic mechanics is that of an observer placed on a train in motion with respect to a station on land, where a second observer is placed. Both observers use the same "meter" to measure the velocity of any object around, and each of them measures a definite value for each velocity, but the measures made by the observer on the train are always different from those made by the observer on land, because of the relative motion between the two RFs. However, there is no problem to pass from one set of measures to the other, since it is a simple operation of composing vectors that are well defined in both RFs. This because in classic mechanics the space-time has the same value in both RFs.

Lorentz and Einstein introduced a "small" variant to this scenario, suggested by experience: contrary to what is predicted by classical mechanics, light propagates at the same speed in both RFs. That is, the observer placed on the train, when measuring the speed of propagation of the light emitted by a source, (whether stationary or in motion with respect to him), finds the same identical value, c , measured by the observer on land. This constitutes a striking violation of the laws of classical mechanics, which requires a radical revision of the classical concept of space-time.

With this condition, they found that the dimensions of an object (an electron for Lorentz, a rod for Einstein) contract in the direction of motion, which means that the space containing those objects "shrinks" in the direction of motion, and the time also slows down (i.e. shrinks) of the same amount in the same direction.

Henceforth the assumption, now a common belief, that the dimensions of space and time decrease in the direction of motion. But this is an incorrect assumption, because it does not specify which space-time is being referred to.

To define a velocity, two subjects are needed: an observer, considered at rest in his RF, and an object in motion relative to him, but considered at rest in its own RF. We therefore have two RFs, that is two distinct space- times, in motion relative to each other. In which of the two the dimensions of the object shrink? In its own RF the object is immobile and therefore unchangeable. Its dimensions shrink only in relation to the observer. This means that its RF, while remaining Cartesian, is reduced with respect to that of the observer.

In conclusion, it is the space-time containing the object in motion that is reduced, not that of the observer, which remains unchanged. The statement that space and time are reduced in the direction of motion, therefore, makes no sense unless it is specified which space-time and respect to which observer.

Returning to the initial problem of defining the mass, we have seen that every definition implies the concept of motion. Lorentz and Einstein show that a mass "shrinks" in the direction of motion for an amount that depends on its velocity, but this velocity has a definite value only in relation to a stationary observer. Therefore, the mass cannot by defined in absolute terms, but only in relation to an observer.

Back to Einstein's rod, what is its real length? It will have a certain value x if the rod is at rest with respect to an observer, meaning that its speed relative to him is null. But if the rod moves with respect to him, its length will decrease as the velocity increases until it is reduced to zero. We must conclude that the rod's length is indeterminate unless we specify with respect to which observer it is measured. It follows that the density of the space-time of an object is indeterminate and collapses to a definite value only in relation to an observer.

This reminds the definition of a quantum object, whose parameters are indeterminate and collapse to a definite value only when measured by an observer. Space-time, then, is a quantum entity.

Two observers in relative motion between them

The invariance of the speed of light's propagation proves that the spacetime is a quantistic entity, because its density is not predetermined, and it has a definite value only when referred to an observer. However, also in this case it still is indetermined, because we don't have an absolute reference against which to compare its value. By mental habit, we assume that the density of space-time is that related to a stationary observer. But stationary with respect to what? There is no absolute space-time reference. We can only verify what is the difference measured by two observers in motion with respect to each other.

At this purpose, let us consider two observers, A and B , in motion with respect to each other at a constant velocity  .

.

Suppose that in the precise instant when the observers, and therefore the origins of the respective RFs, RA and RB, coincide, a flash of light is emitted from that point.

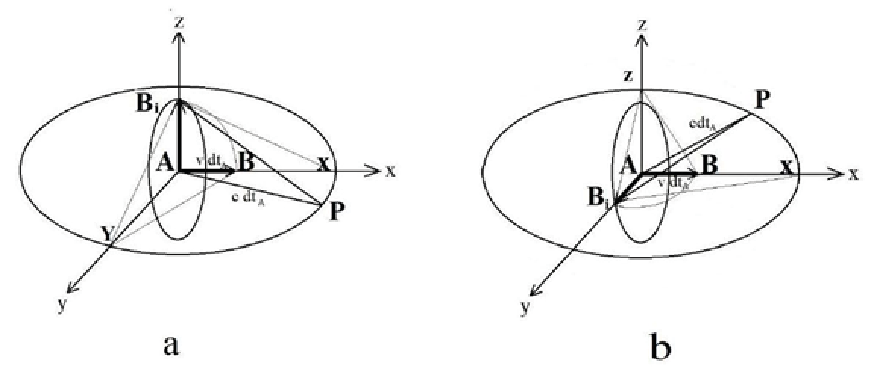

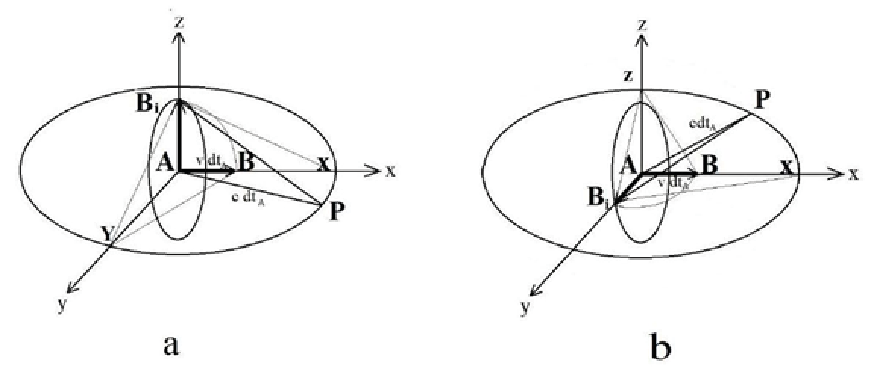

Figure 1: Propagation of a beam of light in a stationary RF, RA and in one in motion, RB

The photons propagate at a same speed, c, in all directions in both RFs, therefore, after a while they will be distributed on the surface of a sphere whose radius is  and center A in RFA, while in RFB the radius is

and center A in RFA, while in RFB the radius is  and the center B.

and the center B.

The surface where the photons are distributed is unique, but it is perceived and described by both observers in a different way, respectively as in Fig.1a and Fig.1b.

Both descriptions are correct and correspond to what the two observers perceive, calculate and measure. In both RFs the laws of Euclidean geometry are valid, and therefore the center of the sphere is unique, all its radius have the same length and the time needed for the light to cover them is always the same. And yet the spherical surface upon which the light is distributed, although unique, has two different centers, A and B, and two different lengths of its radiuses.

This looks a paradoxical situation, because it implies that the two observers, although close to each other, are moving in two different spacetimes. Let's see why and how.

Motion in a two-dimensions Space-Time

Let us consider, in a 2D space-time, an observer B in motion with velocity  with respect to a stationary observer A. Suppose that when B coincides with observer A, a flash of light is emitted from that point.

with respect to a stationary observer A. Suppose that when B coincides with observer A, a flash of light is emitted from that point.

After a while, due to the constancy of the speed of light in both RFs, the photons will be distributed upon a circumference with radius  and center A in RFA and radius

and center A in RFA and radius  in RFB , and center B in RFB (see fig. 1).

in RFB , and center B in RFB (see fig. 1).

Therefore, A and B would be both at the centre of the same circumference. From a geometrical point of view, A and B can have both a constant distance from the same circumference only if they are placed on a line perpendicular to the circumference's plane passing through its centre (Fig. 2). Motion, therefore, must "create" a spatial component such as to move point B along that line.

Figure 2: A and B can have both a constant distance from the same circumference only if  is switched along an imaginary direction

is switched along an imaginary direction

If A is the center of the circle with radius AX = cdtA , we have  and therefore

and therefore  in the stationary RFA ; B is the position, at the time dtA , of the light source in motion.

in the stationary RFA ; B is the position, at the time dtA , of the light source in motion.

The only way to "force" vector  to rotate along a line normal to both, plane

to rotate along a line normal to both, plane  and velocity

and velocity  , is through the following operation:

, is through the following operation:  which can be expressed in function of velocity by applying to vector

which can be expressed in function of velocity by applying to vector  the operator

the operator  which makes it rotate clockwise by 90° (so,

which makes it rotate clockwise by 90° (so,  will coincide with

will coincide with  ).

).

The result is a vector  , which is directed along the imaginary line

, which is directed along the imaginary line  (as the RF has only two dimensions).

(as the RF has only two dimensions).

In this way the center of the circumference where the photons are distributed in RFB is  , and all the radius

, and all the radius  have the same distance from it.

have the same distance from it.

Let's consider the triangle rectangle  we have:

we have:

Motion, therefore, reduces the length of every radius of the circumference in RFB .

Besides:

and finally, as  , we have:

, we have:

In conclusion, if we put  , the transformation equations from the stationary RFA to RFB of the circumference where the photons are distributed are:

, the transformation equations from the stationary RFA to RFB of the circumference where the photons are distributed are:

(1)

(1)

Equivalence to Lorentz' Transformation Equations

From Fig. 2 we can verify that these formulas are equivalent to Lorentz transformation equations:

In fact  ; and because

; and because  ,

,

we have :

Besides  and therefore:

and therefore:

By repeating the same procedure for plane  we also obtain :

we also obtain :

As for the time, its length along  direction is given by the time the light takes to run

direction is given by the time the light takes to run  , that is

, that is  , minus the time necessary to run the length

, minus the time necessary to run the length  , that is

, that is  , and therefore:

, and therefore:

Exactly as in Lorentz' transformation equations. These equations, however, are valid only for the direction,  , i.e. a one-dimensional RF. Therefore it is not correct to assume that they represent the deformation of a 3D RF.

, i.e. a one-dimensional RF. Therefore it is not correct to assume that they represent the deformation of a 3D RF.

Transformation equations in a 3-D Space-Time

Let's now consider the case when a flash of light is emitted by a source moving in a three-dimensions space-time. After a time dtA the photons will be distributed upon a spherical surface with centre A and radius  in RFA and centre B with radius

in RFA and centre B with radius  in RFB .

in RFB .

Vector  in fig. 3 represents the distance between observers A and B in RFA . As we did for a 2-D space-time, in order that both, A and B , have a constant distance from the spherical surface where the photons are distributed (that is to be both at the centre of the sphere), we must rotate

in fig. 3 represents the distance between observers A and B in RFA . As we did for a 2-D space-time, in order that both, A and B , have a constant distance from the spherical surface where the photons are distributed (that is to be both at the centre of the sphere), we must rotate  along the direction

along the direction  .

.

The symbol "  " represents an operator that rotates clockwise of 90° the vector to which it is applied,

" represents an operator that rotates clockwise of 90° the vector to which it is applied,  ; this, then, rotates in all directions laying on the plane normal to

; this, then, rotates in all directions laying on the plane normal to  , passing through the origin (in Fig. 3 the plane yz). With this operation point B shifts to a position

, passing through the origin (in Fig. 3 the plane yz). With this operation point B shifts to a position  .

.

Vector  is perpendicular to planes

is perpendicular to planes  and to

and to  ; therefore, it is twisted along an imaginary direction that cannot be graphically represented in a 3-D reference frame. The "point"

; therefore, it is twisted along an imaginary direction that cannot be graphically represented in a 3-D reference frame. The "point"  , however, is represented in Fig. 3 by the circle with radius

, however, is represented in Fig. 3 by the circle with radius  laying on plane yz, so we can obtain the transformation formulas in the same way as done for a 2-D RF, by shifting

laying on plane yz, so we can obtain the transformation formulas in the same way as done for a 2-D RF, by shifting  through all the positions of the circle.

through all the positions of the circle.

We have  , therefore

, therefore  is the value of every radius of the circle perpendicular to

is the value of every radius of the circle perpendicular to  laying on plane yz.

laying on plane yz.

For  along the direction z (Fig.3,a), every radius

along the direction z (Fig.3,a), every radius  of the circumference laying on plane

of the circumference laying on plane  satisfies the following relations:

satisfies the following relations:

Figure 3: Modification of the space-time in a 3-D reference frame. Motion switches vector  of 900 therefore to all points of the circle

of 900 therefore to all points of the circle

The same relations are satisfied by the circumference of the sphere laying on plane  for

for  directed along y (Fig.3,b). And obviously they are satisfied for all circumferences laying on each plane intermediate between directions z and y, as well as for all other directions until to complete the 360° of the circle.

directed along y (Fig.3,b). And obviously they are satisfied for all circumferences laying on each plane intermediate between directions z and y, as well as for all other directions until to complete the 360° of the circle.

These are the circumferences of the sphere laying on all planes perpendicular to plane yz passing through axis  ; therefore, every radius of the sphere satisfies those relations.

; therefore, every radius of the sphere satisfies those relations.

As  , if we put

, if we put  , we immediately obtain the transformation formulas of the spherical surface where the photons are distributed from RFA to RFB :

, we immediately obtain the transformation formulas of the spherical surface where the photons are distributed from RFA to RFB :

(2)

(2)

which are formally the same obtained for a 2 D space-time.

The first formula is what in mathematic terms is called a complex number, formed by a "real" part plus an "imaginary" part, which means that the RF is displaced towards an imaginary direction for a value v/c. Scientists, for some reason, do not like complex expressions, but this one is inevitable, because the only way to have the same speed of light propagation in two RFs in motion is by displacing on different planes the two RFs.

The Space-Time Shifted Towards an Imaginary Direction

The transformation equations (2) show that the RF of an object in motion is displaced for an amount depending on the relative speed towards an "imaginary" direction, and for that reason both the space and the time are reduced of the same value  with respect to the observer's RF

with respect to the observer's RF

We can have a precise idea of why it happens, visualising the propagation of a flash of light in a 2D RF (fig. 4). If we have a source of light B in motion with respect to the stationary observer A , the source is shifted along the imaginary direction for a value v/c, in position  from where the photons propagate in a 3D RF (

from where the photons propagate in a 3D RF (  ). This propagation intersects the 2D RF (x, y) of the observer in a "lower" position, forming a circle in which the photons still propagate at the speed of light, c , but in a space-time which value is reduced. In fact, we see immediately that

). This propagation intersects the 2D RF (x, y) of the observer in a "lower" position, forming a circle in which the photons still propagate at the speed of light, c , but in a space-time which value is reduced. In fact, we see immediately that  and of course

and of course

Figure 4: The pherical surface where the photons of a source of light B are distributed is "shifted" to Bi along an imagi nary direction, because of motion. Its interference with the 2D RF of the stationary observer is a circumference with a reduced diameter

The same must happen in a 3D RF. Motion displaces the RF of the source in an imaginary direction, and the light expands in that 4D RF (  , i) and intersects the 3D RF (

, i) and intersects the 3D RF (  ) of the observer, forming a sphere of reduced diameter. The result is a reduction, with respect to the observer, of the "density" of the space-time in which the photons propagate.

) of the observer, forming a sphere of reduced diameter. The result is a reduction, with respect to the observer, of the "density" of the space-time in which the photons propagate.

How a stationary observer perceives a mass in motion

It appears that motion does not modify the surface where the photons are distributed, but only the RF (i.e. the space-time) in which they propagate by displacing it into a spatial dimension transverse to the motion.

We therefore conclude that motion does not modify objects, but only the space-time in which they are immersed. However, we cannot "separate" an object from its space. If the space is displaced towards an imaginary dimension, the object too is displaced in the same direction and for the same amount. If the space has a transverse component, the object too must have a component transverse to its motion and a diminished "density" of the same magnitude.

If the object is a mass in motion it will have, with respect to a stationary observer, two components. The first is a mass with a value reduced of the same amount of its space-time, that is

It is a mass responding to Einstein definition of inertial mass, which means that it has "inertia" along the direction of motion (hence the definition of "longitudinal" mass).

The second is a mass "transverse" to the motion,  . The transvers mass is a vectorial magnitude directed along the imaginary dimension; therefore it is not visible by the observer and cannot be represented in a 3D RF. Yet its value can be calculated considering that its module is M

. The transvers mass is a vectorial magnitude directed along the imaginary dimension; therefore it is not visible by the observer and cannot be represented in a 3D RF. Yet its value can be calculated considering that its module is M  and represents a mass switched of 90° with respect to

and represents a mass switched of 90° with respect to  and therefore distributed upon a circle with radius

and therefore distributed upon a circle with radius  , laying on a plane normal to

, laying on a plane normal to  (the circle with radius

(the circle with radius  in fig. 3).

in fig. 3).

Integrating it along that circumference we have:

The transverse mass, therefore, is identified with the kinetic energy of the mass relative to the stationary observer. It does not have dimensions, weight, inertia in the RF of the observer, it is only energy.

So, the space-time of a mass in motion would have two different levels: one at the same level of the stationary observer, "containing" the longitudinal mass, the other on an imaginary dimension "containing" the transverse mass, which is still a mass, but in form of energy, and therefore not visible.

Central Field in motion

A mass in its RF "emanates" a gravitational field, which is a central field. Let's see, then, how a central field (electric, gravitational or whatever else) is perceived by a stationary observer.

For central field we intend a field "connected" to a source A, according to the following law (the same of Newton and Coulomb):

(3)

(3)

At this purpose, we observe that the field is stationary in its own RF , which means that it is immediately established in the totality of it without propagation (or propagating with infinite speed, as often suggested), therefore its lines of force are always directed towards the actual position of A .

However, it is important to keep into consideration that in all calculations the source A (whether a mass or an electric charge) is always considered as a point with no dimensions, while in reality it has a volume that occupies a space-time, which becomes important when the source is in motion.

Let's see then how the field of a source A in motion with linear velocity v is perceived by a stationary observer. Applying the transformation equations (2) to relation (3) we obtain:

In this relation the value of A and the metric of the RF change with the speed, a complication that is useless when  , that is in the majority of mechanical problems. From now on, then, we will ignore the term

, that is in the majority of mechanical problems. From now on, then, we will ignore the term  , reducing this relation to the following:

, reducing this relation to the following:

(4)

(4)

Relation (4) shows that also the field emanated from a source A in motion is a complex magnitude, with a "real" component:

which is still a central field "radiating" from A with a law analogous to the (3), and an "imaginary" component:

This is no more a central field, as its lines of force are circumferences perpendicular to the direction of v . It coincides with the magnetic field (provided that we have a continuous flow of sources A ).

Force between two items of the same nature

If besides a source A we introduce a second source α of the same nature, a force arises between them directed along the line that joins them. If they are both stationary, this force is given by the usual relation:

where  is the distance between them.

is the distance between them.

Let's consider the general case, when both A and α are moving, with respect to the stationary RF of the observer, with velocities  and

and  .

.

Applying the transformation equations (ignoring the terms  we obtain:

we obtain:

This relation shows that the force exerted between the to sources is made by two components. The first is

which is a force directed along the line  joining the longitudinal components of the sources, which value depends only on the distance between them, no matter what their velocities are.

joining the longitudinal components of the sources, which value depends only on the distance between them, no matter what their velocities are.

The second component is an "imaginary" force between the transverse components of the sources and its value depends both on the value and the direction of their velocities:

(5)

(5)

where  and α is the angle between the two imaginary vectors, evidently the same between

and α is the angle between the two imaginary vectors, evidently the same between  and

and  . Therefore, the value of

. Therefore, the value of  would be positive or negative or even null according to that angle.

would be positive or negative or even null according to that angle.

Concluding, while the longitudinal force is always positive and directed along the line that joins the two items, whatever their motion, the transverse force depends not only on the value of the respective velocities, but also on their direction and can be positive or negative if these are concordant or discordant, or null if they are normal to each other.

It is important to note that the longitudinal force acts only vs longitudinal components and the transverse force vs transverse components.

The Gravitational Field

If the source A is a mass, in its RF it emanates a gravitational field:

Where K is the gravitational constant and r the distance from M (considered a point).

If the mass is moving with respect to a stationary observer we have (ignoring the terms  ):

):

which is a field with a "longitudinal" component,  , still a central field analogous to the Newtonian field produced by the stationary mass,

, still a central field analogous to the Newtonian field produced by the stationary mass,

and a "transverse" component

where  is the gravitational constant divided by the speed of light, and

is the gravitational constant divided by the speed of light, and  is the width of the elementary mass considered as a point (that's why the field is expressed as an infinitesimal).

is the width of the elementary mass considered as a point (that's why the field is expressed as an infinitesimal).

This field is the exact equivalent of that produced by a single electric charge in motion  , therefore the term

, therefore the term  , that we can call "current of mass", is the exact equivalent of an elmentary electric current.

, that we can call "current of mass", is the exact equivalent of an elmentary electric current.

The gravito magnetic field

The transvers field of a single electric charge is an "infinitesimal" magnetic field. To have a 3D electro-magnetic field as we know it, it is necessary to have a continuous flow of electric charges, i.e. an electric current. The same for the mass. To have a gravito-magnetic field exactly equivalent to an electro-magnetic field we need to have a continuous flow of masses, that is a current of mass.

It can be achieved, for example, making water flowing in a pipe, in which there will be a "current of mass"  . We can then calculate the gravitomagnetic field using the same formula that Laplace, starting from the results of Biot and Savart's experiments, designed to calculate the magnetic field produced by an electric current flowing in a circuit of whatever form. For a current of mass flowing in a pipe we have:

. We can then calculate the gravitomagnetic field using the same formula that Laplace, starting from the results of Biot and Savart's experiments, designed to calculate the magnetic field produced by an electric current flowing in a circuit of whatever form. For a current of mass flowing in a pipe we have:

where r is the distance of the element ds from point P, while α is the angle between the directions of ds and r. Integrating that formula for a straight pipe of indefinite length we obtain:

where d is the distance from the pipe. This means that the field produced by a current of mass decreases not with the square of the distance, like the gravitational one, but linearly. This is a fundamental property, but that force is much less intense than the newtonian force, as  is the gravitational constant divided by the speed of light. However weak, it exerts a force on a moving mass (and only on it) of the following value:

is the gravitational constant divided by the speed of light. However weak, it exerts a force on a moving mass (and only on it) of the following value:

It shows that a mass moving in a gravito-magnetic field is subject to a force normal to its motion and to the field  , i.e. to a transverse force. (The value of the force acting on a charge in motion in an electromagnetic field has the same form, and was determined experimentally).

, i.e. to a transverse force. (The value of the force acting on a charge in motion in an electromagnetic field has the same form, and was determined experimentally).

The transverse field exerts actions only on entities of the same type, that is transverse masses associated with masses in motion, and their value depends on the angle between the direction of their respective motions. as predicted by relation (5).

Therefore, two parallel pipes attract each other if the flow of water, i.e. the current of mass, runs in the same direction in both of them, they repulse each other if the flows are inversed, but they don't exert any reciprocal action if the pipes are normal to each other, whatever the direction of the flow in them (exactly what happens between to wires run by an electric current).

If we coil two pipes and put one in front of the other, the field produced by each of them is directed along the axis of the coil, and has the following value:

(6)

(6)

where r is the radius of the coil.

The force exerted between the two coils is attractive or repulsive according to the direction of their respective flows.

Of course, the intensity of that force is so weak that probably it would be impossible to realize an instrument capable of measuring it, but we can increase that force by utilizing heavy materials and high speeds.

A metallic ring rotating with angular speed ω is equivalent to a coil run by a current of mass  . Faced to another rotating ring it attracts or repulses it according to their rotation. The same happens with two rotating spherical masses, but only if their axis of rotation is aligned exactly, otherwise they repulse each other.

. Faced to another rotating ring it attracts or repulses it according to their rotation. The same happens with two rotating spherical masses, but only if their axis of rotation is aligned exactly, otherwise they repulse each other.

The lines of flux of the field produced by a rotating body are more or less the same usually represented for the magnetic field produced by a current circulating in a spire, that is lines coming out from the positive pole and closing through the negative.

Figure 5: The gravito-magnetic field produced by a rotating mass.

There is a fundamental difference, however. In a rotating mass not all the lines of flux can close on the opposite pole. In fact, one of the lines generated by each elementary particle of the mass is necessarily parallel to the axis of rotation. Therefore there is a "bundle" of lines of flux that never close to the opposite pole, as they extend in space ad infinitum, never diverging from each other.

Therefore, every rotating body generates, besides a normal gravito-magnetic field, a transvers field which is extended (of course in both directions) indefinitely, inside a "cylinder" with the same diameter of the rotating body.

Through that "cylinder" energy can be transmitted from one side to the other of the universe. For example, if a star is pulsating, its rotational velocity changes with the same frequency of the pulsation, thus generating gravito-magnetic waves that propagate along this cylinder carrying away for indefinite distances the energy spent in the pulsating process.

At this poin we know what kind of actions the transverse mass exerts towards other transvers masses, so we are ready to see how they influence the movements of macroscopic bodies in the universe.

Why the existence of the Dark Matter has been hypothesized

The existence of dark matter has been hypothesized to explain a phenomenon that is observed in all spiral galaxies.

Figure 6: The Pinwheel Galaxy a typical example of spiral galaxy.

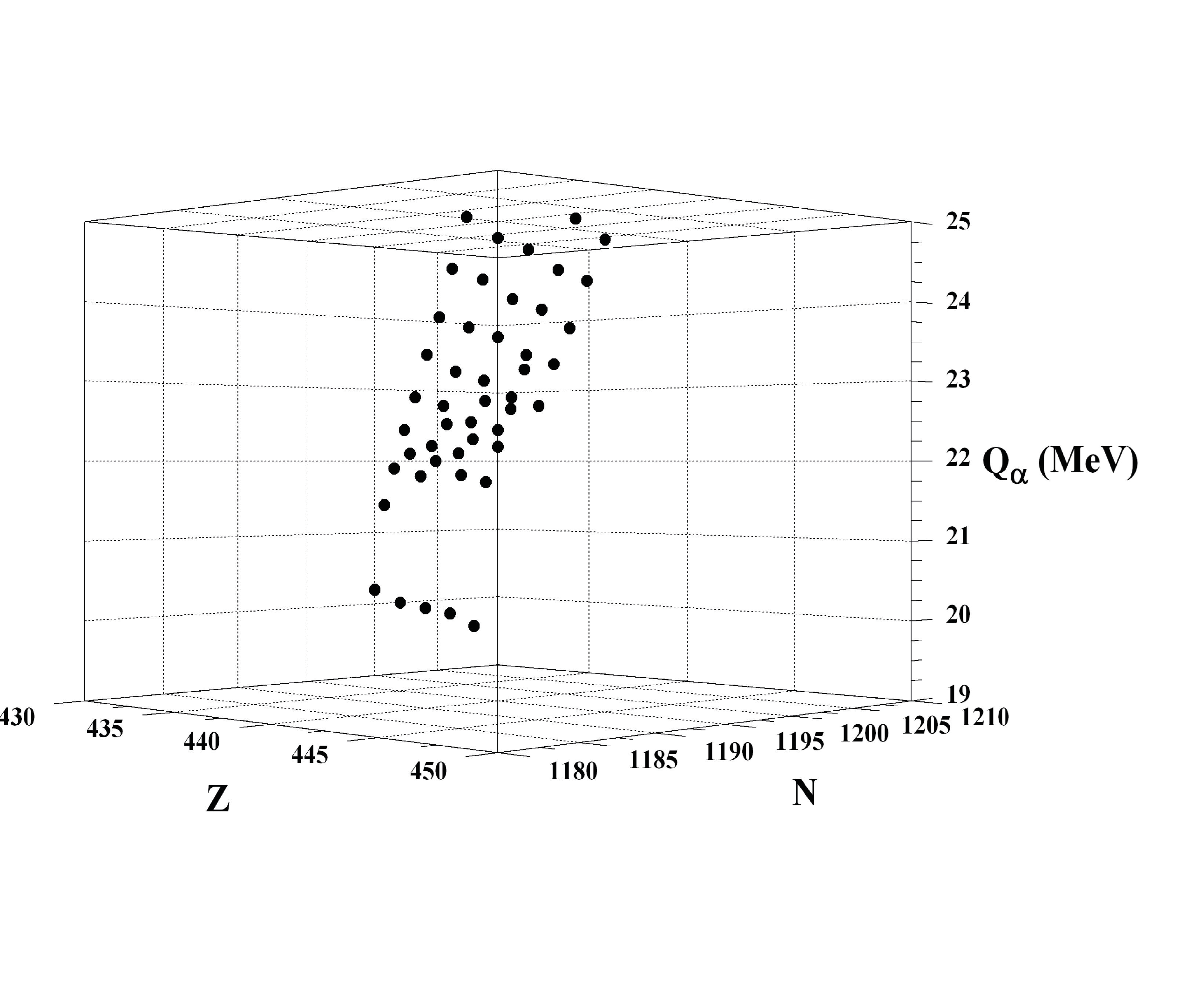

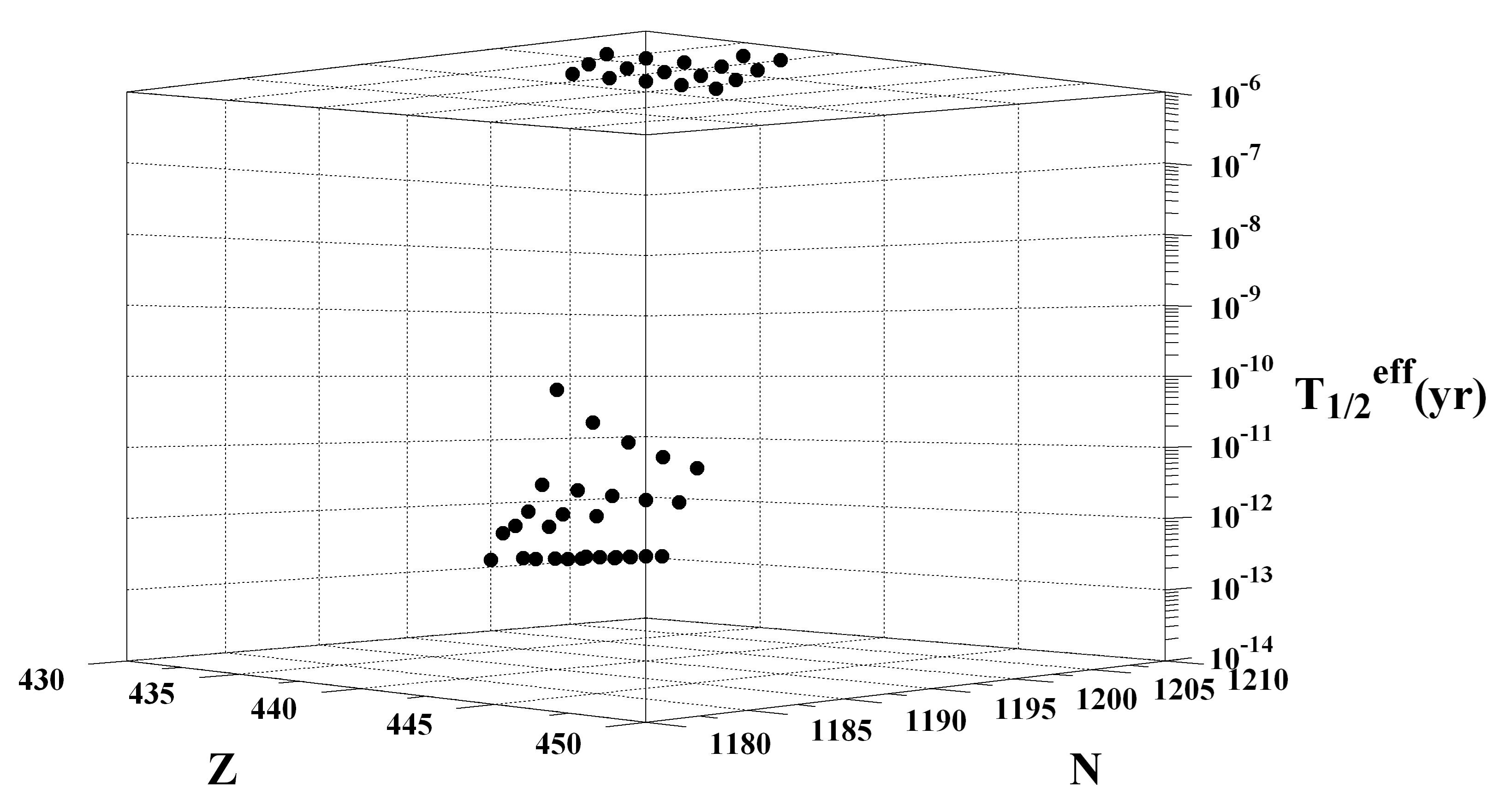

A typical spiral galaxy is made by billions of stars that revolve around a dense center. They are characterized by the fact that the peripheral stars are distributed along arms separated by long distances. The reason for this strange distribution is not known, but apparently astronomers are not bothered too much by that. What more intrigues them is the speed of the stars in these arms, which seems to violate Newton's law. Their speed, in fact, should decrease with the distance from the galaxy's center of rotation, instead from a certain point onwards it becomes constant, as shown by the following figure.

Figure 7: The curve of the speeds of the stars in a typical spiral galaxy: predicted on the base of visible matter .(A) and observed (B). (By Phil Hibbs).

Each star is subject to the centrifugal force,  , that should be balanced by the gravitational force

, that should be balanced by the gravitational force  exerted by the mass of the galaxy. The problem is that the first decreases linearly with the distance from the center of rotation, while the second decreases with the square of the distance, therefore it is not sufficient to keep hold of stars that for some reason would increase, even of a little bit, their velocity. In theory, then, the stars of the arms should disperse into space, because the centrifugal force is stronger than the gravitational force exerted by the entire mass of the galaxy. But they don't. How is this possible?

exerted by the mass of the galaxy. The problem is that the first decreases linearly with the distance from the center of rotation, while the second decreases with the square of the distance, therefore it is not sufficient to keep hold of stars that for some reason would increase, even of a little bit, their velocity. In theory, then, the stars of the arms should disperse into space, because the centrifugal force is stronger than the gravitational force exerted by the entire mass of the galaxy. But they don't. How is this possible?

Necessarily there must be an additional force such as to counterbalance the increase of the centrifugal force. Where does it come from?

The prevailing hypothesis among scientists is that it must be provided by some kind of matter not visible, therefore a dark matter, which manifests itself only through its gravitational action.

How much of it is needed to obtain the desired effect? Apparently, an amazing quantity, which someone evaluates in the order of 80 percent of the entire mass of the universe.

And where should it be? All around the galaxies or inside them, mixed

with the visible stars? Does it rotate with them or is motionless with respect to them, or what else? The only thing that can be reasonably maintained is that it must be strategically placed to provide exactly the extra force necessary to balance the excess of centrifugal force of peripheral stars. Surplus that increases linearly with the distance from the center of rotation, while a Newtonian force, wherever it comes from, decreases with the square of the distance.

An invisible matter, with no mass and inertia and with none of the other characteristics that we attribute to matter in nature, but which is there, placed somewhere and somehow in the firmament, to produce just the necessary force exactly where it is needed to justify the motion of the peripheral stars of the galaxies. No wonder that many scientists are trying to formulate alternative hypothesis, like the "MOND" (Modified Newtonian Dynamics) theory which tries to adjust Newton's law in such a way as to obtain the desired effect. Both these theories, however, do not explain an intriguing characteristic of the spiral galaxies, that the peripheral stars are gathered in separate arms well distanced from each other. Besides they do not explain why it is not present in a significant way in the globular clusters, that do not rotate around themselves.

How the Transverse Mass Explains the Motion of the Stars in the Galaxies

We have seen that every mass in motion has a transverse component, that is a "transverse mass", which produces a gravito-magnetic field that attracts or repulses other transverse masses (always associated with masses in motion) according to the direction of their movement.

Fundamental is the fact that a continuous flow of masses produces a gravito-magnetic field that decreases linearly with the distance from the flow. This means that a star in motion has a "longitudinal" mass that always attracts the surrounding stars with a gravitational force deceasing with the square of the distance, and a "transverse" mass that attracts or repulses (depending on the angle between their velocities) the surrounding stars with a force that decreases linearly with the distance.

At this point, let's see the situation in a rotating galaxy. We have billions of stars revolving around a common center of mass. Inevitably the balance between the Newtonian force (decreasing with the square of the distance from the center of mass) and the centrifugal force (decreasing linearly with the distance from the center of rotation) is broken countless times by the revolving stars, due to their reciprocal interactions, so that a large percentage

of them would move away from the center of rotation and they would disperse into space if it was not for the gravito-magnetic field produced by the gigantic "current of mass" constituted by the flow of the stars.

All of them rotate around the center of the galaxy, so all of them move in the same direction of the nearby stars, therefore, besides the Newtonian force, there is a force of attraction between them produced by the gravitomagnetic field that tends to keep them together. This force, however, is by far smaller than the Newtonian force, therefore, to reach the point of balance they have to move away from the current of mass for a much longer distance. This is why the peripheral stars tend to regroup along lines of equilibrium at a great distance from the stream of the dense core, that is along spiral arms well separated from it. Each arm, in its turn, attracts the stars of the more external arm, preventing them from dispersing into space.

It goes without saying that all the stars in the arms have more or less the same speed, no matter what their distance is from the center of rotation, because both the gravito-magnetic field and the centrifugal force decrease linearly with the distance from the center.

Globular Clusters and Dark Matter

In a spiral galaxy the transverse field produced by the rotation of each star around itself can be neglected, but this field becomes of primary importance in globular clusters, where apparently the dark matter is not present. They are small "galaxies" that do not rotate around themselves, therefore there is no centrifugal force balancing the Newtonian force. In theory they should collapse on themselves, because the longitudinal masses of the stars always attract each other and therefore they should fall on each other. But the collapse does not happen, and the clusters appear to be stable. Why?

The explanation lays on the gravito-magnetic field produced by the rotation of each star around itself (see fig. 5). This field is repulsive. Rotating stars repulse each other with a force that is very weak at long distance, but at short distance it becomes stronger than the Newtonian attractive force. Stars move in the cluster in a presumably chaotic way, like molecules in a gas, but they don't fall on each other thanks to the gravito-magnetic field. The transverse field produced by the rotation of the stars creates a sort of pressure in the cluster that tends to make it expand, while it is kept compact by the gravitational force exerted by the longitudinal masses.

To conclude, what is commonly called "dark matter" would be nothing more than the transverse mass associated with each moving body, a magnitude already predicted by Lorentz and discussed by Einstein in the theory of Special Relativity, but then neglected in the subsequent development of physics. The long and fruitless search for dark matter as a new form of gravitational mass therefore appears destined to bring no results: the transverse mass has all the characteristics attributed to dark matter, but it cannot be detected directly because it manifests itself as energy linked to motion with respect to the observer. This interpretation allows to explain both the "missing mass" and the excess energy observed in the universe, suggesting that the solution to the mystery of dark matter may lie in a conceptual revision of the very notion of mass, rather than in the hypothesis of a new particle or invisible matter.

- Barbiero, F (2022) Dark Matter-Transvers Mass. SCIREA Journal of Astronomy 4.

- Lorentz, H. A (1904) Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity less than that of light. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences 6: 809-831.

- Einstein, A (1905) On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies. Annalen der Physik 17: 891-921.

- Milgrom, M (1983) A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal 270: 365-370.

- Laplace, P. S. (1820) Traite de mecanique celeste. Public domain.

- James Clerk Maxwell (1862) “On physical lines of force". Philosophical Magazine Series 4, 21: 161-175&281-291&338-348.

- Erlichson, Herman (1998) The experiments of Biot and Savart concerning the force exerted by a current on a magnetic needle. American Journal of Physics 66: 389.

- Barbiero, F (2025) The Quantistic Nature of Space-Time, 9th International Conference on Recent advances in Physics (PHY 2025) - International Journal of Recent advances in Physics (IJRAP).

- Spedicato E., Barbiero F (2022) Electro-Magnetic and Gravito-Magnetic Fields as a Result of Modi_cations of the Space-Time Induced by Motion, Beyond Einstein one dimensional approach to special Relativity 21-48.

- Ludwig, G. O (2021-02-23). Galactic rotation curve and dark matter according to gravitomagnetism. The European Physical Journal C 81: 186.

- Bergstrom, Lars (2009). Dark Matter Candidates. New Journal of Physics 11: 105006.

with respect to a stationary observer A. Suppose that when B coincides with observer A, a flash of light is emitted from that point.

with respect to a stationary observer A. Suppose that when B coincides with observer A, a flash of light is emitted from that point.

is switched along an imaginary direction

is switched along an imaginary direction

which makes it rotate clockwise by 90° (so,

which makes it rotate clockwise by 90° (so,  we have:

we have: